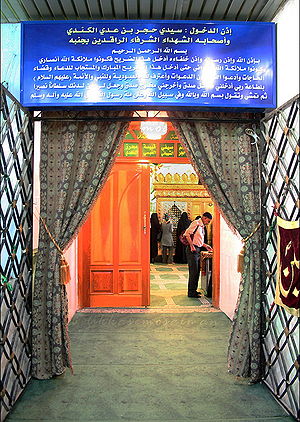

Amr initially halted his campaign at the Babylon Fortress (pictured in 2008), but ultimately forced its Byzantine garrison to evacuate in April 641 after a lengthy siege.

Amr ibn al-AsAmr ibn al-As al-Sahmi (Arabic: عمرو بن العاص, romanized: ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ al-Sahmī; c. 573 – 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in c. 629 and was assigned important roles in the nascent Muslim community by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The first caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) appointed Amr as a commander of the conquest of Syria. He conquered most of Palestine, to which he was appointed governor, and led the Arabs to decisive victories over the Byzantines at the battles of Ajnadayn and Yarmouk in 634 and 636.

Amr launched the conquest of Egypt on his own initiative in late 639, defeating the Byzantines in a string of victories ending with the surrender of Alexandria in 641 or 642. It was the swiftest of the early Muslim conquests and Egypt has remained under Muslim rule since. This was followed by westward advances by Amr as far as Tripoli in present-day Libya. In a treaty signed with the Byzantine governor Cyrus, Amr guaranteed the security of Egypt's population and imposed a poll tax on non-Muslim adult males. He maintained the Coptic-dominated bureaucracy and cordial ties with the Coptic patriarch Benjamin. He founded Fustat as the provincial capital with the mosque later called after him at its center. Amr ruled relatively independently, acquired significant wealth and upheld the interests of the Arab conquerors who formed Fustat's garrison in relation to the central authorities in Medina. Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) dismissed Amr in 646.

After mutineers from Egypt assassinated Uthman, Amr distanced himself from their cause, despite previously instigating opposition against the caliph. In the ensuing First Muslim Civil War, he allied with the governor of Syria, Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, against Caliph Ali (r. 656–661). Amr served as Mu'awiya's representative in the abortive arbitration talks to end the war. Afterward, he wrested control of Egypt from Ali's loyalists and assumed the governorship. Mu'awiya kept him in his post after establishing the Umayyad Caliphate in 661 and Amr ruled the province as a virtual partner of the caliph until his death.

Early life and military careerAmr ibn al-As was born in c. 573.[2] His father, al-As ibn Wa'il, was a wealthy landowner from the Banu Sahm clan of the Quraysh tribe of Mecca.[3] Following al-As' death in c. 622, Amr inherited from him the lucrative al-Waht estate and vineyards near Ta'if.[4] Amr's mother was al-Nabigha bint Harmala from the Banu Jallan clan of the Anaza tribe.[5][6] She had been taken captive and sold, in succession, to several members of the Quraysh, one of whom was Amr's father.[7] As such, Amr had two maternal half-brothers, Amr ibn Atatha of the Banu Adi and Uqba ibn Nafi of the Banu Fihr, and a half-sister from the Banu Abd Shams.[6][7] Amr is physically described in the traditional sources as being short with broad shoulders, having a large head with a wide forehead and wide mouth, long arms and a long beard.[6]

There are conflicting reports about when Amr embraced Islam, with the most credible version placing it in 629/630, not long before the conquest of Mecca by the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[2][8] According to this account, he converted alongside the Qurayshites Khalid ibn al-Walid and Uthman ibn Talha.[8] According to Amr's own testimony, transmitted by his fourth-generation descendant Amr ibn Shu'ayb, he converted in Axum in the presence of King Armah (Najashi) and met Muhammad in Medina upon the latter's return from the Battle of Khaybar in 628.[9] Amr's conversion was conditioned on the forgiveness of his past sins and an "active part in affairs", according to a report cited by the historian Ibn Asakir (d. 1176).[10]

Indeed, in October 629, Amr was tasked by Muhammad with leading the raid on Dhat al-Salasil, likely located in the northern Hejaz (western Arabia), a lucrative opportunity for Amr in view of the potential war spoils.[11] The purpose of the raid is unclear, though the modern historian Fred Donner speculates that it was to "break up a gathering of hostile tribal groups" possibly backed by the Byzantine Empire.[12] The historian Ibn Hisham (d. 833) holds that Amr rallied the nomadic Arabs in the region "to make war on [Byzantine] Syria".[12] The tribal groups targeted in the raid included the Quda'a in general and the Bali specifically.[13] Amr's paternal grandmother hailed from the Bali,[14] and this may have motivated his appointment to the command by Muhammad as Amr was instructed to recruit tribesmen from the Bali and the other Quda'a tribes of Balqayn and Banu Udhra.[13] Following the raid, a delegation of the Bali embraced Islam.[13] Amr further consecrated ties with the tribe by marrying a Bali woman, with whom he had his son Muhammad.[15]

The prophet Muhammad appointed Amr the governor of Oman and he remained there until being informed of Muhammad's death in 632.[16] The death of Muhammad prompted several Arab tribes to defect from the nascent Medina-based Muslim polity in the Ridda wars. Muhammad's successor Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) appointed Amr to rein in the apostate Quda'a tribes, and among those targeted were the Hejazi branches of the Bali.[17] Amr's campaigns, which were supported by the commander Shurahbil ibn Hasana, succeeded in restoring Medina's authority as far as the northern frontier with Syria.[18]

Governor of Palestine and role in the Syrian conquestAmr was one of four commanders dispatched by Abu Bakr to conquer Syria in 633.[19] The focus of Amr's campaign was Palestine, to which he had been appointed governor by Abu Bakr before his departure.[14] He took the coastal route of the Hejaz, reaching Ayla before breaking west into the Negev or possibly the Sinai.[20] He reached the villages of Dathin and Badan in Gaza's environs where he entered into talks with Gaza's Byzantine commander.[20] After the negotiations broke down, Amr's men bested the Byzantines at the Battle of Dathin on 4 February 634 and set up headquarters at Ghamr al-Arabat in the middle of the Wadi Araba.[20][21] Most accounts hold that Amr's army was 3,000-strong; the Muhajirun (emigrants from Mecca to Medina) and the Ansar (natives of Medina), who together formed the core of the earliest Muslim converts, dominated his forces according to al-Waqidi (d. 823), while the 9th-century historian Ibn A'tham holds that Amr's army consisted of 3,300 Qurayshite and allied horsemen, 1,700 horsemen from the Banu Sulaym and 200 from the Yemenite tribe of Madh'hij.[22]

Amr conquered the area around Gaza by February or March 634 and proceeded to besiege Caesarea, the capital of Byzantine Palestine, in July.[23] He soon after abandoned the siege upon the approach of a large Byzantine army.[23] After being reinforced by the remainder of the Muslim armies in Syria, including the new arrivals commanded by Khalid ibn al-Walid, Amr, with overall command of the 20,000-strong Muslim forces, routed the Byzantine army at the Battle of Ajnadayn, the first major confrontation between the Muslims and Byzantium, in July–August 634.[23][24] Amr occupied numerous towns in Palestine, including Bayt Jibrin, Yibna, Amwas, Lydda, Jaffa, Nablus and Sebastia.[25] Most of these localities surrendered after little resistance due to the flight of Byzantine troops; consequently, there is scant information about them in the traditional accounts of the conquest.[26] Abu Bakr's successor Umar (r. 634–644) appointed or confirmed Amr as the commander of the military district of Palestine.[27]

The ravines of the Yarmouk River where Amr kept the Byzantines confined at the decisive Battle of Yarmouk in 636

The Muslims pursued the Byzantine army northward and besieged them at Pella for four months.[28] Amr may have retained overall command of the Muslim armies until this point, though other accounts assign command to Khalid or Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah.[28] In any case, the Muslims landed a heavy blow against the Byzantines in the ensuing Battle of Fahl in December 634 or January 635.[28] Afterward, Amr and Shurahbil may have been sent to besiege Beisan, which capitulated after minor resistance.[29] The Muslims proceeded to besiege Damascus, where the remnants of the Byzantine army from the battles of Ajnadayn and Fahl had gathered. Amr was positioned at the Bab Tuma gate, the Muslim commanders having each been assigned to block one of the city's entrances.[30] By August–September 635, Damascus surrendered to the Muslims.[31] Amr acquired several residences within the city.[32]

In response to the series of defeats, the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) led a large army in person to confront the Muslims; its rout at the Battle of Yarmouk, in which Amr played a key role by confining the Byzantines between the banks of the Yarmouk River and the Yarmouk's ravine, in August–September 636, paved the way for the rest of Syria's conquest by the Muslims.[33] Following Yarmouk, the Muslims attempted to capture Jerusalem, where Amr had previously sent an advance force.[34][35] Abu Ubayda led the siege of Jerusalem, in which Amr participated, but the city only surrendered after Caliph Umar arrived in person to conclude a treaty with its defenders.[34][35] Amr was one of the witnesses of the Treaty of Umar.[36] From Jerusalem,[37] Amr proceeded to besiege and capture the city of Gaza.[38]

First governorship of Egypt

Conquest of Egypt

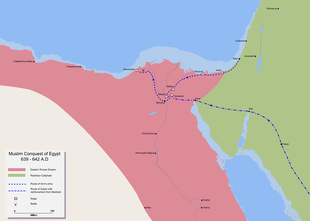

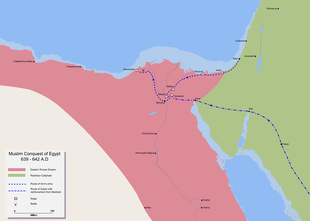

Map detailing the route of Amr and al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam's conquest of Egypt

From his base in southern Palestine, Amr launched the conquest of Byzantine Egypt, where he had established trading interests before his conversion to Islam, making him aware of its importance in international trade.[39][40] The traditional Muslim sources generally hold that Amr undertook the campaign with Caliph Umar's reluctant approval, though a number of accounts hold that he entered the province without Umar's authorization.[2][39] At the head of 4,000 cavalries and with no siege engines, Amr arrived at the frontier town of al-Arish along the northern Sinai coastline on 12 December 639.[39] He captured the strategic Mediterranean port city of Pelusium (al-Farama) following a month-long siege and moved against Bilbeis, which also fell after a month-long siege.[39]

Amr halted his campaign before the fortified Byzantine stronghold of Babylon, at the head of the Nile Delta, and requested reinforcements from Umar.[39] The latter dispatched al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, a leading Qurayshite companion of Muhammad, with a 4,000-strong force, which joined Amr's camp in June 640.[39] Amr retained the supreme command of Arab forces in Egypt.[41] In the following month, his army decisively defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Heliopolis.[39] He captured Memphis soon after and besieged Babylon.[39] During the siege, Amr entered truce negotiations with the Alexandria-based Byzantine governor Cyrus; Emperor Heraclius opposed the talks and recalled Cyrus to Constantinople.[42] Though strong resistance was put up by Babylon's defenders, their morale was sapped after news of Heraclius' death in February 641.[39] Amr made an agreement with the Byzantine garrison, allowing their peaceful withdrawal toward the provincial capital Alexandria on 9 April 641.[43] Amr then sent his lieutenants to conquer different parts of the country.[44] One of them, Kharija ibn Hudhafa, captured the Fayyum oasis, Oxyrhynchus (Bahnasa), Hermopolis (el-Ashmunein) and Akhmim, all in Middle Egypt, and an unspecified number of villages in Upper Egypt.[42][44]

Amr initially halted his campaign at the Babylon Fortress (pictured in 2008), but ultimately forced its Byzantine garrison to evacuate in April 641 after a lengthy siege.

In late 641, Amr besieged Alexandria. It fell virtually without resistance after Cyrus, who had since been restored to office, and Amr finalized a treaty in Babylon guaranteeing the security of Egypt's inhabitants and imposing a poll tax on adult males.[45] The date of the city's surrender was likely November 642.[46] Taking advantage of the uncertain political situation in the wake of Umar's death in 644 and the meager Arab military presence in Alexandria, Emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) dispatched a naval expedition led by a certain Manuel which occupied the city and killed most of its Arab garrison in 645.[47] Alexandria's elite and most of the inhabitants assisted the Byzantines; medieval Byzantine, Coptic and, to a lesser extent, Muslim sources indicate the city was not firmly in Arab hands during the preceding three years.[48] Byzantine forces pushed deeper into the Nile Delta, but Amr forced them back at the Battle of Nikiou. He besieged and captured Alexandria in the summer of 646; most of the Byzantines, including Manuel, were slain, many of its inhabitants were killed and the city was burned until Amr ordered an end to the onslaught.[49] Afterward, Muslim rule in Alexandria was gradually solidified.[50]

In contrast to the disarray of the Byzantine defense, the Muslim forces under Amr's command were unified and organized; Amr frequently coordinated with Caliph Umar and his own troops for all major military decisions.[51] According to the historian Vassilios Christides, Amr "cautiously counterbalanced the superiority in numbers and equipment of the Byzantine army by applying skillful military tactics" and despite the lack of "definite, prepared, long-term plans ... the Arab army moved with great flexibility as the occasion arose".[52] In the absence of siege engines, Amr oversaw long sieges of heavily fortified Byzantine positions, most prominently Babylon, cut supply lines and engaged in long wars of attrition.[52] He made advantageous use out of the nomads in his ranks, who were seasoned in hit-and-run tactics, and his settled troops, who were generally more acquainted with siege warfare.[52] His cavalry-dominated army moved through Egypt's deserts and oases with relative ease.[52] Moreover, political circumstances became more favorable to Amr with the death of the hawkish Heraclius and his short-term replacement with the more pacifist Heraklonas and Martina.[52]

Expeditions in Cyrenaica and TripolitaniaAfter the surrender of Alexandria in 642, Amr marched his army westward, bypassing the fortified Byzantine coastal strongholds of Paraetonium (Marsa Matruh), Appolonia Sozusa (Marsa Soussa) and Ptolemais (Tolmeita), capturing Barca and reaching Torca in Cyrenaica.[53] Toward the end of the year, Amr launched a second cavalry assault targeting Tripoli. The city was heavily fortified by the Byzantines and contained several naval vessels in its harbor.[53] Due to his lack of siege engines, he employed the lengthy siege tactic used in the Egyptian conquest.[53] After about a month, his troops entered Tripoli through a vulnerable point in its walls and sacked the city.[53] Its fall, which entailed the evacuation by sea of the Byzantine garrison and most of the population, is dated to 642 or 643/44. Though the Arab hold over Cyrenaica and Zawila to the far south remained firm for decades except for a short-lived Byzantine occupation in 690, Tripoli was recaptured by the Byzantines a few years after Amr's entry.[53] The region was definitively conquered by the Arabs during the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705).

Administration

The courtyard of the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in 2013. The mosque was originally founded by Amr in 641 but was redesigned and expanded significantly over the next several centuries.

The exterior wall of the mosque in 2011

The exterior wall of the mosque in 2011Amr "regulated the government of the country [Egypt], administration of justice and the imposition of taxes", according to the historian A. J. Wensinck.[2] During his siege of Babylon, Amr had erected an encampment near the fortress.[54] He originally intended for Alexandria to serve as the Arabs' capital in Egypt, but Umar rejected this on the basis that no body of water, i.e. the Nile, should separate the caliph from his army.[55][56][57][b] Instead, following Alexandria's surrender, in 641 or 642,[59] Amr made his encampment near Babylon the permanent garrison town (miṣr) of Fustat, the first town founded by the Arabs in Egypt.[60][61][62] Its location along the eastern bank of the Nile River and at the head of the Nile Delta and edge of the Eastern Desert strategically positioned it to dominate the Upper and Lower halves of Egypt.[54] Fustat's proximity to Babylon, where Amr also established an Arab garrison, afforded the Arab settlers a convenient means to employ and oversee the Coptic bureaucratic officials who inhabited Babylon and proved critical to running the day-to-day affairs of the Arab government.[63][56]

Amr had the original tents of Fustat replaced with mud brick and baked brick dwellings.[60] Documents found in Hermopolis (el-Ashmunein) dating from the 640s confirm official orders to forward building materials to Babylon to construct the new city.[64] The city was organized into allotments over an area stretching 5–6 kilometers (3.1–3.7 mi) along the Nile and 1–2 kilometers (0.62–1.24 mi) inland to the east.[56] The allotments were distributed among the components of Amr's army, with priority given to the Quraysh, the Ansar and Amr's personal guard, the 'Ahl al-Rāya' (People of the Banner),[56] which included several Bali tribesmen as a result of their kinship and marital ties to Amr.[15] An opposing theory holds that Amr did not assign the plots; rather, the tribes staked their own claims.[65] Amr established a commission to resolve the ensuing land disputes.[66] At the center of the new capital Amr built a congregational mosque, later known as the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As; the original structure was frequently redesigned and expanded between its foundation and its final form in 827.[63] Amr had his own dwelling built immediately east of the mosque and it most likely served as his government headquarters.[64]

In the northwestern part of Alexandria, Amr built a hilltop congregational mosque, later called after him,[67] before the Byzantine occupation of 645/46, after which he built a second called the Mosque of Mercy;[68] neither mosque has been presently identified.[69] Adjacent to the congregational mosque, Amr took personal ownership of a fort, which he later donated for government use.[70] This part of the city became the administrative and social core of Arab settlement in Alexandria.[71] Accounts vary as to the number of troops Amr garrisoned in the city, ranging from 1,000 soldiers from the Azd and Banu Fahm tribes to a quarter of the army which was replaced on a rotational basis every six months.[72]

As per the 641 treaty with Cyrus, Amr imposed a poll tax of two gold dinars on non-Muslim adult males.[73] He imposed other measures, sanctioned by Umar, that entailed the inhabitants' regular provision of wheat, honey, oil and vinegar as a subsistence allowance for the Arab troops.[74] He had these goods stored in a distribution warehouse called dār al-rizq.[73] After taking a census of the Muslims, he further ordered that each Muslim be annually supplied by the inhabitants a highly embroidered wool robe (Egyptian robes were prized by the Arabs), a burnous, a turban, a sirwal (trousers) and shoes.[74] In a Greek papyrus dated to 8 January 643 and containing Amr's seal (a fighting bull), Amr (transliterated as "Ambros") requests fodder for his army's animals and bread for his soldiers from an Egyptian village.[75] According to the historian Martin Hinds, there is "no evidence" that Amr "did anything to streamline the cumbersome fiscal system taken over from the Byzantines; rather, the upheavals of conquest can only have made the system more open to abuse than ever".[76]

After entering Alexandria, Amr invited the Coptic patriarch Benjamin to return to the city after his years of exile under Cyrus.[77] The patriarch maintained close ties with Amr and restored the monasteries of Wadi el-Natrun, including the Saint Macarius Monastery, which functions until the present-day.[77] According to the historian Hugh N. Kennedy, "Benjamin played a major role in the survival of the Coptic Church through the transition to Arab rule".[78]#fastitlinks.com