AL AQSA MASQUE

Al-Aqsa Mosque Not to be confused with the Temple Mount, often referred to as the Al Aqsa Compound.

Al-Aqsa Mosque

ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ

Al-Masjid al-’Aqṣā

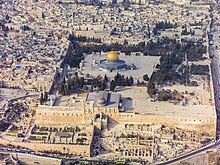

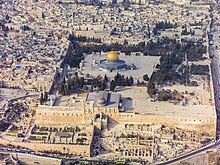

Old City of Jerusalem

Lcation within the Old City of Jerusalem

Administration

Jerusalem Islamic Waqf

Geographic coordinates

Architecture

Type

Mosque

Style

Early Islamic, Mamluk

Date established

705 CE

Specifications

Direction of façade

north-northwest

Capacity

5,000+

Dome(s)

two large + tens of smaller ones

Minaret(s)

four

Minaret height

37 meters (121 ft) (tallest)

Materials

Limestone (external walls, minaret, facade) stalactite (minaret), Gold, lead and stone (domes), white marble (interior columns) and mosaic[1]

Part of a series on

Al-Aa Mosque (Arabic: ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ, romanized: al-Masjid al-ʾAqṣā, IPA: [ʔælˈmæsdʒɪd ælˈʔɑqsˤɑ] (

listen), "the Farthest Mosque"), located in the Old City of Jerusalem, is the third holiest site in Islam. The mosque was built on top of the Temple Mount, known as the Al Aqsa Compound or Haram esh-Sharif in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad was transported from the Sacred Mosque in Mecca to al-Aqsa during the Night Journey. Islamic tradition holds that Muhammad led prayers towards this site until the 17th month after his migration from Mecca to Medina, when Allāh directed him to turn towards the Kaaba in Mecca.

listen), "the Farthest Mosque"), located in the Old City of Jerusalem, is the third holiest site in Islam. The mosque was built on top of the Temple Mount, known as the Al Aqsa Compound or Haram esh-Sharif in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad was transported from the Sacred Mosque in Mecca to al-Aqsa during the Night Journey. Islamic tradition holds that Muhammad led prayers towards this site until the 17th month after his migration from Mecca to Medina, when Allāh directed him to turn towards the Kaaba in Mecca.The covered mosque building was originally a small prayer house erected by Umar, the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, but was rebuilt and expanded by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik and finished by his son al-Walid in 705 CE. The mosque was completely destroyed by an earthquake in 746 and rebuilt by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur in 754. It was rebuilt again in 780. Another earthquake destroyed most of al-Aqsa in 1033, but two years later the Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir built another mosque whose outline is preserved in the current structure. The mosaics on the arch at the qibla end of the nave also go back to his time.

During the periodic renovations undertaken, the various ruling dynasties of the Islamic Caliphate constructed additions to the mosque and its precincts, such as its dome, facade, its minbar, minarets and the interior structure. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, they used the mosque as a palace and the Dome of the Rock as a church, but its function as a mosque was restored after its recapture by Saladin in 1187. More renovations, repairs and additions were undertaken in the later centuries by the Ayyubids, Mamluks, Ottomans, the Supreme Muslim Council, and Jordan. Today, the Old City is under Israeli control, but the mosque remains under the administration of the Jordanian/Palestinian-led Islamic Waqf.

The mosque is located in close proximity to historical sites significant in Judaism and Christianity, most notably the site of the Second Temple, the holiest site in Judaism. As a result, the area is highly sensitive, and has been a flashpoint in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[2]

History

Pre-construction

The mosque is located on the Temple Mount, referred to by Muslims today as the "Haram al-Sharif" ("Noble Sanctuary"), an enclosure expanded by King Herod the Great beginning in 20 BCE.[10] In Islamic tradition, the original sanctuary is believed to date to the time of Abraham.[11]

The mosque resides on an artificial platform that is supported by arches constructed by Herod's engineers to overcome the difficult topographic conditions resulting from the southward expansion of the enclosure into the Tyropoeon and Kidron valleys.[12] At the time of the Second Temple, the present site of the mosque was occupied by the Royal Stoa, a basilica running the southern wall of the enclosure.[12] The Royal Stoa was destroyed along with the Temple during the sacking of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE.

It was once thought that Emperor Justinian's "Nea Ekklesia of the Theotokos", or the New Church of the God-Bearer, dedicated to the God-bearing Virgin Mary, consecrated in 543 and commonly known as the Nea Church, was situated where al-Aqsa Mosque was later constructed. However, remains identified as those of the Nea Church were uncovered in the south part of the Jewish Quarter in 1973.[13][14]

Analysis of the wooden beams and panels removed from the mosque during renovations in the 1930s shows they are made from Cedar of Lebanon and cypress. Radiocarbon dating indicates a large range of ages, some as old as 9th-century BCE, showing that some of the wood had previously been used in older buildings.[15]

During his excavations in the 1930s, Robert Hamilton uncovered portions of a multicolor mosaic floor with geometric patterns, but didn't publish them.[16] The date of the mosaic is disputed: Zweig considers that they are from the pre-Islamic Byzantine period, while Baruch, Reich and Sandghaus favor a much later Umayyad origin on account of their similarity to a known Umayyad mosaic.[16]

Construction by the Umayyads

The mosque along the southern wall of al-Haram al-Sharif

The current construction of the al-Aqsa Mosque is dated to the early Umayyad period of rule in Palestine. Architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell, referring to a testimony by Arculf, a Gallic monk, during his pilgrimage to Palestine in 679–82, notes the possibility that the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, Umar ibn al-Khattab, erected a primitive quadrangular building for a capacity of 3,000 worshipers somewhere on the Haram ash-Sharif. However, Arculf visited Palestine during the reign of Mu'awiyah I, and it is possible that Mu'awiyah ordered the construction, not Umar. This latter claim is explicitly supported by the early Muslim scholar al-Muthahhar bin Tahir.[17]

According to several Muslim scholars, including Mujir ad-Din, al-Suyuti, and al-Muqaddasi, the mosque was reconstructed and expanded by the caliph Abd al-Malik in 690 along with the Dome of the Rock.[17][18] Guy le Strange claims that Abd al-Malik used materials from the destroyed Church of Our Lady to build the mosque and points to possible evidence that substructures on the southeast corners of the mosque are remains of the church.[18] In planning his magnificent project on the Temple Mount, which in effect would turn the entire complex into the Haram al-Sharif ("the Noble Sanctuary"), Abd al-Malik wanted to replace the slipshod structure described by Arculf with a more sheltered structure enclosing the qibla ("direction"), a necessary element in his grand scheme. However, the entire Haram al-Sharif was meant to represent a mosque. How much he modified the aspect of the earlier building is unknown, but the length of the new building is indicated by the existence of traces of a bridge leading from the Umayyad palace just south of the western part of the complex. The bridge would have spanned the street running just outside the southern wall of the Haram al-Sharif to give direct access to the mosque. Direct access from palace to mosque was a well-known feature in the Umayyad period, as evidenced at various early sites. Abd al-Malik shifted the central axis of the mosque some 40 meters (130 ft) westward, in accord with his overall plan for the Haram al-Sharif. The earlier axis is represented in the structure by the niche still known as the "mihrab of 'Umar." In placing emphasis on the Dome of the Rock, Abd al-Malik had his architects align his new al-Aqsa Mosque according to the position of the Rock, thus shifting the main north–south axis of the Noble Sanctuary, a line running through the Dome of the Chain and the Mihrab of Umar.[19]

In contrast, Creswell, while referring to the Aphrodito Papyri, claims that Abd al-Malik's son, al-Walid I, reconstructed the Aqsa Mosque over a period of six months to a year, using workers from Damascus. Most scholars agree that the mosque's reconstruction was started by Abd al-Malik, but that al-Walid oversaw its completion. In 713–14, a series of earthquakes ravaged Jerusalem, destroying the eastern section of the mosque, which was subsequently rebuilt during al-Walid's rule. In order to finance its reconstruction, al-Walid had gold from the dome of the Rock minted to use as money to purchase the material.[17] The Umayyad-built al-Aqsa Mosque most likely measured 112 x 39 meters.[19]

Earthquakes and reconstructions

In 746, the al-Aqsa Mosque was damaged in an earthquake, four years before as-Saffah overthrew the Umayyads and established the Abbasid Caliphate. The second Abbasid caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur declared his intent to repair the mosque in 753, and he had the gold and silver plaques that covered the gates of the mosque removed and turned into dinars and dirhams to finance the reconstruction which ended in 771. A second earthquake damaged most of al-Mansur's repairs, excluding those made in the southern portion in 774.[18][20] In 780, His successor Muhammad al-Mahdi had it rebuilt, but curtailed its length and increased its breadth.[18][21] Al-Mahdi's renovation is the first known to have written records describing it.[22] In 985, Jerusalem-born Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi recorded that the renovated mosque had "fifteen naves and fifteen gates".[20]

The doors of the Saladin Minbar, early 1900s. The minbar was built on Nur al-Din's orders, but installed by Saladin

In 1033, there was another earthquake, severely damaging the mosque. The Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir rebuilt and completely renovated the mosque between 1034 and 1036. The number of naves was drastically reduced from 15 to seven.[20] Az-Zahir built the four arcades of the central hall and aisle, which presently serve as the foundation of the mosque. The central aisle was double the width of the other aisles and had a large gable roof upon which the dome—made of wood—was constructed.[17] Persian geographer, Nasir Khusraw describes the Aqsa Mosque during a visit in 1047:

The Haram Area (Noble Sanctuary) lies in the eastern part of the city; and through the bazaar of this (quarter) you enter the Area by a great and beautiful gateway (Dargah)... After passing this gateway, you have on the right two great colonnades (Riwaq), each of which has nine-and-twenty marble pillars, whose capitals and bases are of colored marbles, and the joints are set in lead. Above the pillars rise arches, that are constructed, of masonry, without mortar or cement, and each arch is constructed of no more than five or six blocks of stone. These colonnades lead down to near the Maqsurah (enclosure).[23]

Jerusalem was captured by the Crusaders in 1099, during the First Crusade. They named the mosque "Solomon's Temple", distinguishing it from the Dome of the Rock, which they named Templum Domini (Temple of God). While the Dome of the Rock was turned into a Christian church under the care of the Augustinians,[24] the al-Aqsa Mosque was used as a royal palace and also as a stable for horses. In 1119, it was transformed into the headquarters of the Templar Knights. During this period, the mosque underwent some structural changes, including the expansion of its northern porch, and the addition of an apse and a dividing wall. A new cloister and church were also built at the site, along with various other structures.[25] The Templars constructed vaulted western and eastern annexes to the building; the western currently serves as the women's mosque and the eastern as the Islamic Museum.[20]

After the Ayyubids under the leadership of Saladin reconquered Jerusalem following the siege of 1187, several repairs and renovations were undertaken at al-Aqsa Mosque. In order to prepare the mosque for Friday prayers, within a week of his capture of Jerusalem Saladin had the toilets and grain stores installed by the Crusaders at al-Aqsa removed, the floors covered with precious carpets, and its interior scented with rosewater and incense.[26] Saladin's predecessor—the Zengid sultan Nur al-Din—had commissioned the construction of a new minbar or "pulpit" made of ivory and wood in 1168–69, but it was completed after his death; Nur ad-Din's minbar was added to the mosque in November 1187 by Saladin.[27] The Ayyubid sultan of Damascus, al-Mu'azzam, built the northern porch of the mosque with three gates in 1218. In 1345, the Mamluks under al-Kamil Shaban added two naves and two gates to the mosque's eastern side.[20]

Mid-19th century chromolithograph of the mosque

After the Ottomans assumed power in 1517, they did not undertake any major renovations or repairs to the mosque itself, but they did to the Noble Sanctuary as a whole. This included the building of the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527), the restoration of the Pool of Raranj, and the building of three free-standing domes—the most notable being the Dome of the Prophet built in 1538. All construction was ordered by the Ottoman governors of Jerusalem and not the sultans themselves.[28] The sultans did make additions to existing minarets, however.[28] In 1816, the mosque was restored by Governor Sulayman Pasha al-Adil after having been in a dilapidated state.[29]

Modern era

See also: Al-Aqsa Intifada

The dome of the mosque in 1982. It was made of aluminum (and looked like silver), but replaced with its original lead plating in 1983.

A man prays in the mosque in 2008

The first renovation in the 20th century occurred in 1922, when the Supreme Muslim Council under Amin al-Husayni (the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem) commissioned Turkish architect Ahmet Kemalettin Bey to restore al-Aqsa Mosque and the monuments in its precincts. The council also commissioned British architects, Egyptian engineering experts and local officials to contribute to and oversee the repairs and additions which were carried out in 1924–25 by Kemalettin. The renovations included reinforcing the mosque's ancient Umayyad foundations, rectifying the interior columns, replacing the beams, erecting a scaffolding, conserving the arches and drum of the main dome's interior, rebuilding the southern wall, and replacing timber in the central nave with a slab of concrete. The renovations also revealed Fatimid-era mosaics and inscriptions on the interior arches that had been covered with plasterwork. The arches were decorated with gold and green-tinted gypsum and their timber tie beams were replaced with brass. A quarter of the stained glass windows also were carefully renewed so as to preserve their original Abbasid and Fatimid designs.[30] Severe damage was caused by the 1837 and 1927 earthquakes, but the mosque was repaired in 1938 and 1942.[20]

On July 20, 1951, King Abdullah I was shot three times by a Palestinian gunman as he entered the mosque, killing him. His grandson Prince Hussein, was at his side and was also hit, though a medal he was wearing on his chest deflected the bullet.

The mosque seen from the Western Wall plaza, 2005

On 21 August 1969, a fire was started by a visitor from Australia named Denis Michael Rohan. Rohan was a member of an evangelical Christian sect known as the Worldwide Church of God.[31] He hoped that by burning down al-Aqsa Mosque he would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus, making way for the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount. Rohan was subsequently hospitalized in a mental institution.[32] In response to the incident, a summit of Islamic countries was held in Rabat that same year, hosted by Faisal of Saudi Arabia, the then king of Saudi Arabia. The al-Aqsa fire is regarded as one of the catalysts for the formation of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in 1972.[33]

In the 1980s, Ben Shoshan and Yehuda Etzion, both members of the Gush Emunim Underground, plotted to blow up the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Etzion believed that blowing up the two mosques would cause a spiritual awakening in Israel, and would solve all the problems of the Jewish people. They also hoped the Third Temple of Jerusalem would be built on the location of the mosque.[34][35] On 15 January 1988, during the First Intifada, Israeli troops fired rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters outside the mosque, wounding 40 worshipers.[36][37] On 8 October 1990, 22 Palestinians were killed and over 100 others injured by Israeli Border Police during protests that were triggered by the announcement of the Temple Mount Faithful, a group of religious Jews, that they were going to lay the cornerstone of the Third Temple.[38][39]

On 28 September 2000, then-opposition leader of Israel Ariel Sharon and members of the Likud Party, along with 1,000 armed guards, visited the al-Aqsa compound; a large group of Palestinians went to protest the visit. After Sharon and the Likud Party members left, a demonstration erupted and Palestinians on the grounds of the Haram al-Sharif began throwing stones and other projectiles at Israeli riot police. Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at the crowd, injuring 24 people. The visit sparked a five-year uprising by the Palestinians, commonly referred to as the al-Aqsa Intifada, though some commentators, citing subsequent speeches by PA officials, particularly Imad Falouji and Arafat himself, claim that the Intifada had been planned months in advance, as early as July upon Yasser Arafat's return from Camp David talks.[40][41][42] On 29 September, the Israeli government deployed 2,000 riot police to the mosque. When a group of Palestinians left the mosque after Friday prayers (Jumu'ah,) they hurled stones at the police. The police then stormed the mosque compound, firing both live ammunition and rubber bullets at the group of Palestinians, killing four and wounding about 200.[43]

On 5 November 2014, Israeli police entered Al-Aqsa for the first time since capturing Jerusalem in 1967, said Sheikh Azzam Al-Khatib, director of the Islamic Waqf. Previous media reports of 'storming Al-Aqsa' referred to the Haram al-Sharif compound rather than the Al-Aqsa mosque itself.[44]

Architecture

The mosque is situated at the Southern end of the Haram ash-Sharif

The rectangular al-Aqsa Mosque and its precincts cover 14.4 hectares (36 acres), although the mosque itself is about 12 acres (5 ha) in area and can hold up to 5,000 worshippers.[45] It is 83 m (272 ft) long, 56 m (184 ft) wide.[45] Unlike the Dome of the Rock, which reflects classical Byzantine architecture, the Al-Aqsa Mosque is characteristic of early Islamic architecture.[46]

Dome

The silver-colored dome consists of lead sheeting

Nothing remains of the original dome built by Abd al-Malik. The present-day dome was built by az-Zahir and consists of wood plated with lead enamelwork.[17] In 1969, the dome was reconstructed in concrete and covered with anodized aluminium, instead of the original ribbed lead enamel work sheeting. In 1983, the aluminium outer covering was replaced with lead to match the original design by az-Zahir.[47]

Beneath the dome is the Al-Qibli Chapel (Arabic: المصلى القبلي al-Musalla al-Qibli); also known as al-Jami' al-Qibli Arabic: الجامع القِبْلي, a Muslim prayer hall, located in the southern part of the mosque.[48] It was built by the Rashidun caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab in 637 CE.

Al-Aqsa's dome is one of the few domes to be built in front of the mihrab during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, the others being the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (715) and the Great Mosque of Sousse (850).[49] The interior of the dome is painted with 14th-century-era decorations. During the 1969 burning, the paintings were assumed to be irreparably lost, but were completely reconstructed using the trateggio technique, a method that uses fine vertical lines to distinguish reconstructed areas from original ones.[47]

Facade and porch

The facade of the mosque. It was constructed by the Fatimids, then expanded by the Crusaders, the Ayyubids and the Mamluks

The facade of the mosque was built in 1065 CE on the instructions of the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. It was crowned with a balustrade consisting of arcades and small columns. The Crusaders damaged the facade, but it was restored and renovated by the Ayyubids. One addition was the covering of the facade with tiles.[20] The second-hand material of the facade's arches includes sculpted, ornamental material taken from Crusader structures in Jerusalem.[50] The facade consists of fourteen stone arches,[3][dubious – discuss] most of which are of a Romanesque style. The outer arches added by the Mamluks follow the same general design. The entrance to the mosque is through the facade's central arch.[51]

The porch is located at the top of[dubious – discuss] the facade. The central bays of the porch were built by the Knights Templar during the First Crusade,[dubious – discuss] but Saladin's nephew al-Mu'azzam Isa ordered the construction of the porch itself in 1217.[20][dubious – discuss]

Interior

The al-Aqsa Mosque has seven aisles of hypostyle naves with several additional small halls to the west and east of the southern section of the building.[21] There are 121 stained glass windows in the mosque from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. About a fourth of them were restored in 1924.[30] The mosaic decoration and the inscription (two lines just above the decoration near the roof as visible in the photos placed in the gallery here) on the spandrels of arche facing main entrance near main dome area which date back to Fatimid period were revealed from behind plaster work of a later date that covered them.[52] Name of Fatimid Imam is clearly visible in end part of the first line of inscription and continued in second line.

History

Pre-construction

The mosque is located on the Temple Mount, referred to by Muslims today as the "Haram al-Sharif" ("Noble Sanctuary"), an enclosure expanded by King Herod the Great beginning in 20 BCE.[10] In Islamic tradition, the original sanctuary is believed to date to the time of Abraham.[11]

The mosque resides on an artificial platform that is supported by arches constructed by Herod's engineers to overcome the difficult topographic conditions resulting from the southward expansion of the enclosure into the Tyropoeon and Kidron valleys.[12] At the time of the Second Temple, the present site of the mosque was occupied by the Royal Stoa, a basilica running the southern wall of the enclosure.[12] The Royal Stoa was destroyed along with the Temple during the sacking of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE.

It was once thought that Emperor Justinian's "Nea Ekklesia of the Theotokos", or the New Church of the God-Bearer, dedicated to the God-bearing Virgin Mary, consecrated in 543 and commonly known as the Nea Church, was situated where al-Aqsa Mosque was later constructed. However, remains identified as those of the Nea Church were uncovered in the south part of the Jewish Quarter in 1973.[13][14]

Analysis of the wooden beams and panels removed from the mosque during renovations in the 1930s shows they are made from Cedar of Lebanon and cypress. Radiocarbon dating indicates a large range of ages, some as old as 9th-century BCE, showing that some of the wood had previously been used in older buildings.[15]

During his excavations in the 1930s, Robert Hamilton uncovered portions of a multicolor mosaic floor with geometric patterns, but didn't publish them.[16] The date of the mosaic is disputed: Zweig considers that they are from the pre-Islamic Byzantine period, while Baruch, Reich and Sandghaus favor a much later Umayyad origin on account of their similarity to a known Umayyad mosaic.[16]

Construction by the Umayyads

The mosque along the southern wall of al-Haram al-Sharif

The current construction of the al-Aqsa Mosque is dated to the early Umayyad period of rule in Palestine. Architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell, referring to a testimony by Arculf, a Gallic monk, during his pilgrimage to Palestine in 679–82, notes the possibility that the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, Umar ibn al-Khattab, erected a primitive quadrangular building for a capacity of 3,000 worshipers somewhere on the Haram ash-Sharif. However, Arculf visited Palestine during the reign of Mu'awiyah I, and it is possible that Mu'awiyah ordered the construction, not Umar. This latter claim is explicitly supported by the early Muslim scholar al-Muthahhar bin Tahir.[17]

According to several Muslim scholars, including Mujir ad-Din, al-Suyuti, and al-Muqaddasi, the mosque was reconstructed and expanded by the caliph Abd al-Malik in 690 along with the Dome of the Rock.[17][18] Guy le Strange claims that Abd al-Malik used materials from the destroyed Church of Our Lady to build the mosque and points to possible evidence that substructures on the southeast corners of the mosque are remains of the church.[18] In planning his magnificent project on the Temple Mount, which in effect would turn the entire complex into the Haram al-Sharif ("the Noble Sanctuary"), Abd al-Malik wanted to replace the slipshod structure described by Arculf with a more sheltered structure enclosing the qibla ("direction"), a necessary element in his grand scheme. However, the entire Haram al-Sharif was meant to represent a mosque. How much he modified the aspect of the earlier building is unknown, but the length of the new building is indicated by the existence of traces of a bridge leading from the Umayyad palace just south of the western part of the complex. The bridge would have spanned the street running just outside the southern wall of the Haram al-Sharif to give direct access to the mosque. Direct access from palace to mosque was a well-known feature in the Umayyad period, as evidenced at various early sites. Abd al-Malik shifted the central axis of the mosque some 40 meters (130 ft) westward, in accord with his overall plan for the Haram al-Sharif. The earlier axis is represented in the structure by the niche still known as the "mihrab of 'Umar." In placing emphasis on the Dome of the Rock, Abd al-Malik had his architects align his new al-Aqsa Mosque according to the position of the Rock, thus shifting the main north–south axis of the Noble Sanctuary, a line running through the Dome of the Chain and the Mihrab of Umar.[19]

In contrast, Creswell, while referring to the Aphrodito Papyri, claims that Abd al-Malik's son, al-Walid I, reconstructed the Aqsa Mosque over a period of six months to a year, using workers from Damascus. Most scholars agree that the mosque's reconstruction was started by Abd al-Malik, but that al-Walid oversaw its completion. In 713–14, a series of earthquakes ravaged Jerusalem, destroying the eastern section of the mosque, which was subsequently rebuilt during al-Walid's rule. In order to finance its reconstruction, al-Walid had gold from the dome of the Rock minted to use as money to purchase the material.[17] The Umayyad-built al-Aqsa Mosque most likely measured 112 x 39 meters.[19]

Earthquakes and reconstructions

In 746, the al-Aqsa Mosque was damaged in an earthquake, four years before as-Saffah overthrew the Umayyads and established the Abbasid Caliphate. The second Abbasid caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur declared his intent to repair the mosque in 753, and he had the gold and silver plaques that covered the gates of the mosque removed and turned into dinars and dirhams to finance the reconstruction which ended in 771. A second earthquake damaged most of al-Mansur's repairs, excluding those made in the southern portion in 774.[18][20] In 780, His successor Muhammad al-Mahdi had it rebuilt, but curtailed its length and increased its breadth.[18][21] Al-Mahdi's renovation is the first known to have written records describing it.[22] In 985, Jerusalem-born Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi recorded that the renovated mosque had "fifteen naves and fifteen gates".[20]

The doors of the Saladin Minbar, early 1900s. The minbar was built on Nur al-Din's orders, but installed by Saladin

In 1033, there was another earthquake, severely damaging the mosque. The Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir rebuilt and completely renovated the mosque between 1034 and 1036. The number of naves was drastically reduced from 15 to seven.[20] Az-Zahir built the four arcades of the central hall and aisle, which presently serve as the foundation of the mosque. The central aisle was double the width of the other aisles and had a large gable roof upon which the dome—made of wood—was constructed.[17] Persian geographer, Nasir Khusraw describes the Aqsa Mosque during a visit in 1047:

The Haram Area (Noble Sanctuary) lies in the eastern part of the city; and through the bazaar of this (quarter) you enter the Area by a great and beautiful gateway (Dargah)... After passing this gateway, you have on the right two great colonnades (Riwaq), each of which has nine-and-twenty marble pillars, whose capitals and bases are of colored marbles, and the joints are set in lead. Above the pillars rise arches, that are constructed, of masonry, without mortar or cement, and each arch is constructed of no more than five or six blocks of stone. These colonnades lead down to near the Maqsurah (enclosure).[23]

Jerusalem was captured by the Crusaders in 1099, during the First Crusade. They named the mosque "Solomon's Temple", distinguishing it from the Dome of the Rock, which they named Templum Domini (Temple of God). While the Dome of the Rock was turned into a Christian church under the care of the Augustinians,[24] the al-Aqsa Mosque was used as a royal palace and also as a stable for horses. In 1119, it was transformed into the headquarters of the Templar Knights. During this period, the mosque underwent some structural changes, including the expansion of its northern porch, and the addition of an apse and a dividing wall. A new cloister and church were also built at the site, along with various other structures.[25] The Templars constructed vaulted western and eastern annexes to the building; the western currently serves as the women's mosque and the eastern as the Islamic Museum.[20]

After the Ayyubids under the leadership of Saladin reconquered Jerusalem following the siege of 1187, several repairs and renovations were undertaken at al-Aqsa Mosque. In order to prepare the mosque for Friday prayers, within a week of his capture of Jerusalem Saladin had the toilets and grain stores installed by the Crusaders at al-Aqsa removed, the floors covered with precious carpets, and its interior scented with rosewater and incense.[26] Saladin's predecessor—the Zengid sultan Nur al-Din—had commissioned the construction of a new minbar or "pulpit" made of ivory and wood in 1168–69, but it was completed after his death; Nur ad-Din's minbar was added to the mosque in November 1187 by Saladin.[27] The Ayyubid sultan of Damascus, al-Mu'azzam, built the northern porch of the mosque with three gates in 1218. In 1345, the Mamluks under al-Kamil Shaban added two naves and two gates to the mosque's eastern side.[20]

Mid-19th century chromolithograph of the mosque

After the Ottomans assumed power in 1517, they did not undertake any major renovations or repairs to the mosque itself, but they did to the Noble Sanctuary as a whole. This included the building of the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527), the restoration of the Pool of Raranj, and the building of three free-standing domes—the most notable being the Dome of the Prophet built in 1538. All construction was ordered by the Ottoman governors of Jerusalem and not the sultans themselves.[28] The sultans did make additions to existing minarets, however.[28] In 1816, the mosque was restored by Governor Sulayman Pasha al-Adil after having been in a dilapidated state.[29]

Modern era

See also: Al-Aqsa Intifada

The dome of the mosque in 1982. It was made of aluminum (and looked like silver), but replaced with its original lead plating in 1983.

A man prays in the mosque in 2008

The first renovation in the 20th century occurred in 1922, when the Supreme Muslim Council under Amin al-Husayni (the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem) commissioned Turkish architect Ahmet Kemalettin Bey to restore al-Aqsa Mosque and the monuments in its precincts. The council also commissioned British architects, Egyptian engineering experts and local officials to contribute to and oversee the repairs and additions which were carried out in 1924–25 by Kemalettin. The renovations included reinforcing the mosque's ancient Umayyad foundations, rectifying the interior columns, replacing the beams, erecting a scaffolding, conserving the arches and drum of the main dome's interior, rebuilding the southern wall, and replacing timber in the central nave with a slab of concrete. The renovations also revealed Fatimid-era mosaics and inscriptions on the interior arches that had been covered with plasterwork. The arches were decorated with gold and green-tinted gypsum and their timber tie beams were replaced with brass. A quarter of the stained glass windows also were carefully renewed so as to preserve their original Abbasid and Fatimid designs.[30] Severe damage was caused by the 1837 and 1927 earthquakes, but the mosque was repaired in 1938 and 1942.[20]

On July 20, 1951, King Abdullah I was shot three times by a Palestinian gunman as he entered the mosque, killing him. His grandson Prince Hussein, was at his side and was also hit, though a medal he was wearing on his chest deflected the bullet.

The mosque seen from the Western Wall plaza, 2005

On 21 August 1969, a fire was started by a visitor from Australia named Denis Michael Rohan. Rohan was a member of an evangelical Christian sect known as the Worldwide Church of God.[31] He hoped that by burning down al-Aqsa Mosque he would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus, making way for the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount. Rohan was subsequently hospitalized in a mental institution.[32] In response to the incident, a summit of Islamic countries was held in Rabat that same year, hosted by Faisal of Saudi Arabia, the then king of Saudi Arabia. The al-Aqsa fire is regarded as one of the catalysts for the formation of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in 1972.[33]

In the 1980s, Ben Shoshan and Yehuda Etzion, both members of the Gush Emunim Underground, plotted to blow up the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Etzion believed that blowing up the two mosques would cause a spiritual awakening in Israel, and would solve all the problems of the Jewish people. They also hoped the Third Temple of Jerusalem would be built on the location of the mosque.[34][35] On 15 January 1988, during the First Intifada, Israeli troops fired rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters outside the mosque, wounding 40 worshipers.[36][37] On 8 October 1990, 22 Palestinians were killed and over 100 others injured by Israeli Border Police during protests that were triggered by the announcement of the Temple Mount Faithful, a group of religious Jews, that they were going to lay the cornerstone of the Third Temple.[38][39]

On 28 September 2000, then-opposition leader of Israel Ariel Sharon and members of the Likud Party, along with 1,000 armed guards, visited the al-Aqsa compound; a large group of Palestinians went to protest the visit. After Sharon and the Likud Party members left, a demonstration erupted and Palestinians on the grounds of the Haram al-Sharif began throwing stones and other projectiles at Israeli riot police. Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at the crowd, injuring 24 people. The visit sparked a five-year uprising by the Palestinians, commonly referred to as the al-Aqsa Intifada, though some commentators, citing subsequent speeches by PA officials, particularly Imad Falouji and Arafat himself, claim that the Intifada had been planned months in advance, as early as July upon Yasser Arafat's return from Camp David talks.[40][41][42] On 29 September, the Israeli government deployed 2,000 riot police to the mosque. When a group of Palestinians left the mosque after Friday prayers (Jumu'ah,) they hurled stones at the police. The police then stormed the mosque compound, firing both live ammunition and rubber bullets at the group of Palestinians, killing four and wounding about 200.[43]

On 5 November 2014, Israeli police entered Al-Aqsa for the first time since capturing Jerusalem in 1967, said Sheikh Azzam Al-Khatib, director of the Islamic Waqf. Previous media reports of 'storming Al-Aqsa' referred to the Haram al-Sharif compound rather than the Al-Aqsa mosque itself.[44]

Architecture

The mosque is situated at the Southern end of the Haram ash-Sharif

The rectangular al-Aqsa Mosque and its precincts cover 14.4 hectares (36 acres), although the mosque itself is about 12 acres (5 ha) in area and can hold up to 5,000 worshippers.[45] It is 83 m (272 ft) long, 56 m (184 ft) wide.[45] Unlike the Dome of the Rock, which reflects classical Byzantine architecture, the Al-Aqsa Mosque is characteristic of early Islamic architecture.[46]

Dome

The silver-colored dome consists of lead sheeting

Nothing remains of the original dome built by Abd al-Malik. The present-day dome was built by az-Zahir and consists of wood plated with lead enamelwork.[17] In 1969, the dome was reconstructed in concrete and covered with anodized aluminium, instead of the original ribbed lead enamel work sheeting. In 1983, the aluminium outer covering was replaced with lead to match the original design by az-Zahir.[47]

Beneath the dome is the Al-Qibli Chapel (Arabic: المصلى القبلي al-Musalla al-Qibli); also known as al-Jami' al-Qibli Arabic: الجامع القِبْلي, a Muslim prayer hall, located in the southern part of the mosque.[48] It was built by the Rashidun caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab in 637 CE.

Al-Aqsa's dome is one of the few domes to be built in front of the mihrab during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, the others being the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (715) and the Great Mosque of Sousse (850).[49] The interior of the dome is painted with 14th-century-era decorations. During the 1969 burning, the paintings were assumed to be irreparably lost, but were completely reconstructed using the trateggio technique, a method that uses fine vertical lines to distinguish reconstructed areas from original ones.[47]

Facade and porch

The facade of the mosque. It was constructed by the Fatimids, then expanded by the Crusaders, the Ayyubids and the Mamluks

The facade of the mosque was built in 1065 CE on the instructions of the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. It was crowned with a balustrade consisting of arcades and small columns. The Crusaders damaged the facade, but it was restored and renovated by the Ayyubids. One addition was the covering of the facade with tiles.[20] The second-hand material of the facade's arches includes sculpted, ornamental material taken from Crusader structures in Jerusalem.[50] The facade consists of fourteen stone arches,[3][dubious – discuss] most of which are of a Romanesque style. The outer arches added by the Mamluks follow the same general design. The entrance to the mosque is through the facade's central arch.[51]

The porch is located at the top of[dubious – discuss] the facade. The central bays of the porch were built by the Knights Templar during the First Crusade,[dubious – discuss] but Saladin's nephew al-Mu'azzam Isa ordered the construction of the porch itself in 1217.[20][dubious – discuss]

Interior

The al-Aqsa Mosque has seven aisles of hypostyle naves with several additional small halls to the west and east of the southern section of the building.[21] There are 121 stained glass windows in the mosque from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. About a fourth of them were restored in 1924.[30] The mosaic decoration and the inscription (two lines just above the decoration near the roof as visible in the photos placed in the gallery here) on the spandrels of arche facing main entrance near main dome area which date back to Fatimid period were revealed from behind plaster work of a later date that covered them.[52] Name of Fatimid Imam is clearly visible in end part of the first line of inscription and continued in second line.#fastitlinks.com

No comments:

Post a Comment